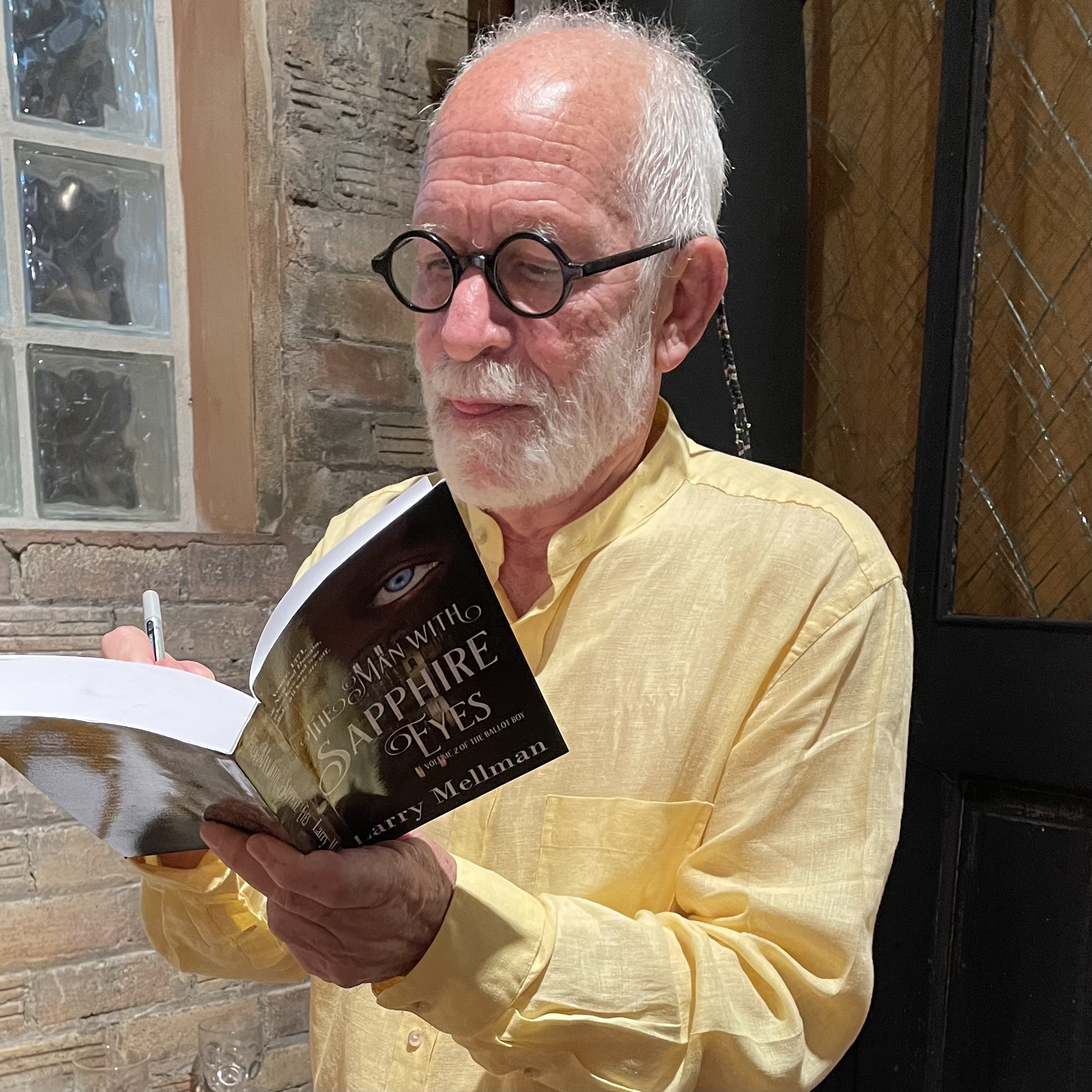

The Man with Sapphire Eyes Launch Party

Mouse over or swipe image below to view slideshow controls

Thank you all for coming. In addition to thanking you, I must also offer thanks to the natural world which daily convinces me it can survive the human onslaught, and endure, and thrive, with or without us. Hopefully with us, and the glories of our history.

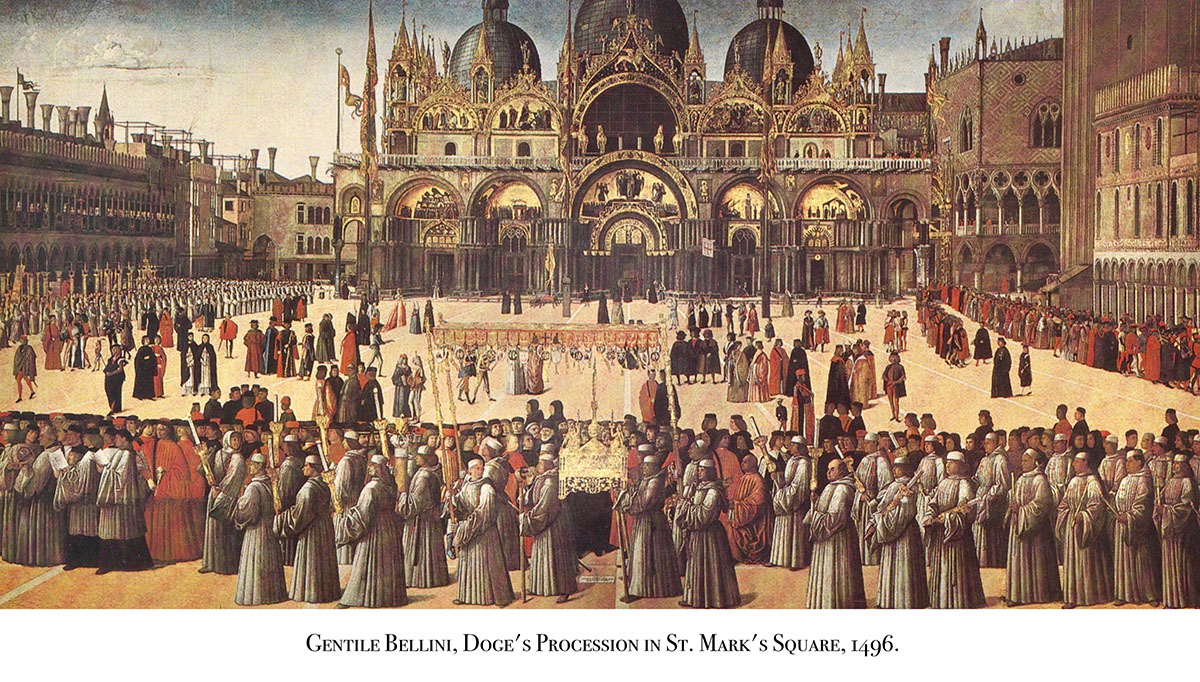

One rainy day in Venice I took refuge in the Museo Correr on St. Mark’s Square. Originally built as Napoleon’s residence after his conquest of Venice in 1797, the so-called Napoleonic Wing was opened as a museum of Venetian art and history in 1836. Sprawling, palatial, with myriad galleries filled with treasures, the museum proved the perfect place to spend a rainy day.

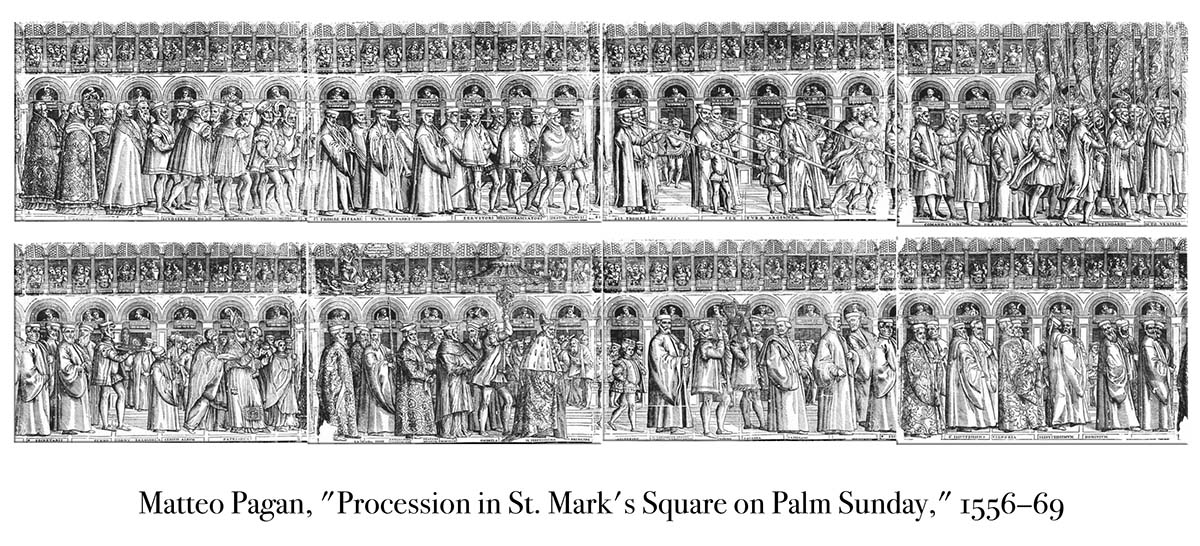

I found myself in a long, narrow gallery I had never noticed before, displaying a row of eight woodblock prints, two-feet wide and over a foot tall, a total of sixteen-feet, presenting a continuous image, meticulous in its detail, of a ducal procession on Easter Sunday in 1556. You can see them here.

The procession began with silver and gold trumpets and trombones, followed by pages, squires, knights, more musicians, priests and canons, generals, admirals, the cream of the Venetian nobility. In the center, two pages carried the doge’s stool and gold cushion while another held a gold umbrella over the doge’s head. The doge was followed with another eight feet of visiting ambassadors, senators and assorted nobles. Immediately preceding of the doge, a young boy strutted proudly, seeming curiously out of place and raising the question, “what’s he doing there?” His label read “ballotino.” Ballot Boy.

As I scratched my head over this, a tour group came into the room to view the Procession. I stepped aside so they could see better and without missing a beat, the tour guide, seeing where I stared in puzzlement, pointed at the Ballottino and said, “This the ballot counter. He tallied the votes in the election of the Doge. His job was to keep the nobles honest. By law he had to be a commoner no older than 14, selected at random to circumvent cheating by the noble families. Once chosen, he was taken from his family and installed in the Doge’s Palace where he remained in the Doge’s service until the Doge died.”

I was hooked. I needed to know more. And like all things Venetian, the story turned out to be as complex and fascinating as the city and took years to unravel, which is how The Ballot Boy began.

The setting of my Ballot Boy trilogy, both time, 1368-1380, and place, is unusual. Few people realize that the Venetian republic lasted for a thousand years, the longest-standing republic in history. Over the centuries its structure was endlessly tweaked to create a perfect machine to maintain itself, uninterrupted, which, for the most part, worked. No internal squabbles, noble slugfests, or civil wars disrupted the orderly transfer of power from one doge to the next. That peaceful transition was the wonder of its time, eyed by every monarch in Europe, but also concealed a seething cauldron of intrigue often beset by wars. The notoriously complex electoral system was expressly designed to prevent the seizure of power by one family and the emergence of a tyrant. The elections, which included several rounds of randomness (by lot instead of voting), prevented the highjacking of elections, particularly that of the doge, but every significant official in the republic was elected within a complex architecture of committees. Hence the importance, real and symbolic, of the ballot boy, chosen at random the morning of the ducal election, which forms the first chapter of The Ballot Boy.

During the fourteenth and fifteen centuries, Venice was the richest city in Europe, the emporium for the wealth of Asia, with an unparalleled fleet commanding a vast mercantile empire extending from the Black Sea to the North Sea, dependent on her peerless navy both to move commerce and to safeguard it. Her wealth made Venice the target of multiple enemies, from neighboring Padua, to other Italian city-states, to Hungary, Spain, and the Islamic empires of the East.

The Man With Sapphire Eyes tells the story of the desperate war between Venice and neighboring Padua allied militarily with King Louis the Great of Hungary to smash the Venetian Republic.

Now, here’s John Pull to read the first chapter of The Man With Sapphire Eyes, volume 2 of the Ballot Boy trilogy.